|

Guy Faux; Or, The Gunpowder Treason An Historical

Melo-Drama,

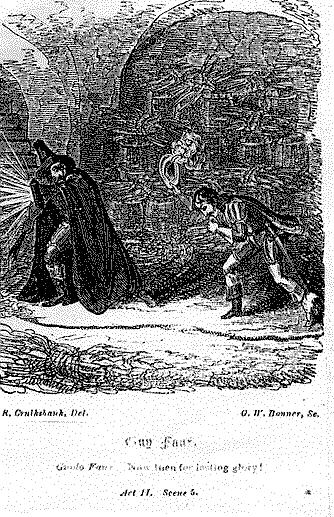

Or, The Gunpowder Treason An Historical Melo-Drama, In Three Acts, By George Macfarren, (Original Transcription by Conrad and Mary Bladey ©2002) Author of "My Old Woman," Winning a Husband, Lestocq &c. Printed from the Acting Copy, with Remarks, Biographical and Critical, By D.—G. To which are added, A Description of the Costume, --Cast of the Characters Entrances and Exits, --Relative Positions of the Performers on the Stage, and the whole of the stage Business. As performed at the Metropolitan Minor Theatre. Embellished with a Fine Engraving, By Mr. Bonner, from a Drawing taken in the Theatre, by Mr. R. Cruikshank. London: John Cumberland& Son 2, Cumberland Terrace Camden New Town Guy Faux. The dramatist acts wisely who selects a popular subject whereon to exercise his art. Goblin tales—rare and incredible adventures by sea and land-are admirable materials to excite wonder, and fix attention. That which pleased us in youth naturally claims sympathy in our riper years. We may question the existence of such a monster as Bluebeard, and criticize the veracity of those daring adventurers, Sinbad and Baron Munchausen; yet, while we renounce the fiction, we retain the charm, and cordially welcome our old friends, from whom we have been parted for many a long year:-- Talk of our youthful days in merry vein, And act our sports and gambols o’er again; For many a sport had I , at many a time, In youth’s gay spring, when life was in its prime! The story of Guy Faux has the double advantage of being marvelous and true. It forms a prominent feature in English history; and is sufficiently removed from our own times to give it a romantic interest, and beget a superstitious reverence in the million. The memory of this popular conspirator is duly invoked from one end of the kingdom to the other--celebrations and rejoicings, with a liberal ignition of that article which gives its name to his plot, hail his re-appearance: though a bitter foe to Parliaments, he is annually chaired—hence he bids fair to partake of that immortality which has ever been assigned to deeds of daring. Guy Faux comes before us with considerable improvement as to personal appearance: he is no longer a mere paste-board incendiary, a king of squibs and crackers! His queer wig and horrible mask are reformed altogether; and we now behold him, for aught we know to the contrary, in his habit, as he lived. Certain of his acquaintance, who had been wont to contemplate his true effigy, were puzzled to recognize their ancient friend, thus transmogrified and regenerated. Like the virtuoso’s shield, he had been scrubbed and scoured, and some of his value (in their eyes) might have been rubbed off with his rust. It was, however, necessary, in this age of improvement, to set matters right respecting "Old Guy"—to exhibit him- "A fine gay, bold-fac’d villain, as thou see’st him"— at the Coburg Theatre, and not the old scarecrow (worthy, indeed, of his supporters!) that has hitherto solicited our bounty through our remembrance. Having with becoming seriousness, attempted to vindicate the modern, or rather ( for Mr. O. Smith is but the restoration of Guy Faux) the ancient appearance of our friend we proceed to notice the historical melodrama in which he is made to play so distinguished a part. Addison, in compliance with the taste of the age, introduced the loves of Juba and Marcia into his tragedy; and the author of Guy Faux, probably for the same reason, has reinforced his gunpowder plot with the marriage, and other family misfortunes, of Walter Tresham and Eleanor, the sister of the gay Lord Mounteagle. Scorned by his wife’s relations, and disinherited by his own father, Walter Tresham resolves to quit France, where for some time he had lived in great poverty, and once more try to better his fortunes in his native land. He returns to England, calls upon his old friend, Master Hugh Piercy, at his mansion on the banks of the Thames, near to the Parliament House, and is received, not as "friend remembered not," but with a generous welcome. Both are sadly changed since last they met: poverty, sorrow, and the world’s rude buffeting, have stamped their impression on the features of the one; deep thought and anxious care have been equally busy with those of the other. But philosophy had not made Piercy a recluse; he had thought and reasoned like the noble conspirator of Venice:-- "I am a villain, To see the sufferings of my fellow creatures, And own myself a man; to see our senators Cheat the deluded people with a show of liberty, which yet they ne’er must taste of." He was, therefore, planning that treason which, in his opinion, was to destroy the regal and aristocratical tyranny of the land, and he eagerly waited the arrival of the daring spirit who was to carry it into execution. Having been sworn to secrecy, Walter Tresham is made acquainted with the plot. He trembles at the responsibility he has unwarily incurred, and resolves to save Lord Monteagle, his brother-in-law, from the general destruction. He threfore writes the celebrated letter, which history has handed down to us, to warn him of his danger, and muffled up in disguise, delivers it with his own hand. He is watched and pursued to his miserable lodging, but is saved by his wife, who hides him behind the arras, and, by her steady firmness, quiets the suspicious of the pursuer. The hour approaches when King James, seated on his throne, is to open the Parliament. The last stroke of twelve is the appointed signal—the drums and trumpets of the royal procession are already heard at a distance, when Walter Tresham, ascending from the vault, is recognized by Lord Mounteagle as the stranger who the preceding night had delivered him the mysterious letter. The conspirator again warns Monteagle of his danger, and escapes. The interior of the vault is now discovered, with Guy Faux making the train: the clock begins to strike—the twelfth stroke of the bell is heard—he fires the train—when Mounteagle rushes in, and, with admirable presence of mind, sweeps away part of the train with his hat, and cuts off the communication! The seizure of Guy Faux—his examination before King James and hi s council—and his solemn procession to execution, follow. He dies as he had lived--a cruel, impious, and remorseless villain. The comic portion of this piece is in the rival loves of Lord Mounteagle and Sir Tristram Collywobble, for the Lady Alice, ward of King James. The gay lord-the Cornish knight, of Gander Hall—the merry lady—and the pedantic, and somewhat pusillanimous, monarch, are amusing. James’s mortal aversion to a naked sword ("Haud, ‘tis a roasting-spit!!")—his frequent reference to the classics ("But Greek is of nae use at present") –his self-importance and good-nature, are all kept within due bounds. The Gander Knight loses the Lady Alice, who is bestowed on Monteagle as the reward of his service; and, having previously deposited three bottles of Canary under his doublet, is married, under favour of a mask, to Dame Margaret, the old Scotch nurse! The piece concludes with the death of the conspirators, and the explosion of a barrel of gunpowder- when (to adopt a well-known theatrical phrase) "a picture is formed, and the curtain falls." From the above sketch, it will be seen how far the author of Guy Faux has availed himself of history. ON the stage, this drama was very effective. The characteristic representation of the hero, by Mr. O. Smith, was quite sufficient to insure it popularity. D.___G. To return to the top click here The Conductors of this work print no plays but those which they have seen acted. The Stage Directions are given from personal observations during the most recent performances. Exits and Entrances. R. means Right; L, Left, F. the Flat, or Scene running across the back of the Stage; D.F. door in Flat; R.D. Right door; L. D. Left Door; S.E. Second Entrance; U.E. Upper entrance; C. D. Centre Door, Relative Positions R. Means Right; L, Left; C. Centre; R.C. Right of Centre;L.C. Left of Centre. R. RC. C. LC. L. ***The Reader is supposed to be on the Stage, facing the Audience. King James.—Crimson velvet cloak—doublet—trunks, with gold lace—purple silk puffs-red hose—russet shoes-hat and feathers. Earl of Suffolk.—Green doublet and trunks, with gold lace and white puffs-white hose and shoes. Earl of Pembroke- Purple ibid. Lord Monteagle- Puce doublet and cloak, richly spangled—white satin puffs- white hat and feathers—trunks and hose.. Sir Tristram Collywobble- White doublet and trunks, extravagantly full-blue puffs and cloak, with silver lace-blue hat—white feathers- white hose and shoes—large blue rosettes. Guido Faux—Dark-brown doublet and trunks, puffed with

scarlet—large scarlet cloak—black high crowned hat—feathers-red pantaloons—high

topped russet boots.

Walter Tresham- Gray doublet and trunks, trimmed with black velvet—large roqueleure-=black hat and feathers-russet boots. Master Richard Catesby.-Scarlet doublet and trunks, with blue puffs and buttons—russet boots-gauntlets—high hat and feathers. Sir Everard Digby.—Green velvet ibid—pink puffs. Master Hugh Piercy.—Brown ibid-orange puffs. Master Robert Winter.—Fawn- colored ibid.-crimson puffs. Rockwood.—Amber ibid. Grant.-Puce ibid. Caies-Blue ibid. Sheriff-Large scarlet claok. Yeoman.- Beefeater’s dress. Elinor.-Slate-coloured muslin dress-long black veil. Lady Alice—White satin, with points and beads-blue silk mantle. Dame Margaret.—Black satin, with points—red silk mantle. As performed at the Royal Coburg Theatre. Original April 9, 1830

Click here to return to the top

Guy Faux Act I. Scene I.-Piercy’s Mansion and Gardens on the banks of the Thames, near to the Parliament House, Westminster, with a view of the opposite shore, Lambeth Palace, &c.—A gate, L.S.E., supposed to lead out of an alley.—A knocking heard at the gate. Enter Stephen, L.S.E., followed by Master Hugh Piercy, hastily. Pie.(Stopping him.) Ho! Stay thee, Stephen: I will attend the gate myself. Who can it be would gain an entrance at this early hour? Well, sirrah, why dost wait? Get thee to roost, this nightly watching makes thee stupid—away! (Exit Stephen, R.S.E.—Knocking again.) Who is it so unmannerly to knock me up at sunrise? Walter Tresham. (Without.) An old and true friend, though a poor one, would speak with MasterPpercy. Pie. Folks call me Piercy; but I know thee not. I have no traces of thy face within my memory: yet in these degenerate times, friendship is so rare, that even its professors should be prized. Enter, and let me view thee closer. (Opens the gate.) Enter Walter Tresham, at the gate, L.S.E. Wal. Has poverty and care, strange climate, and the world’s rude buffeting, so changed me, that my old friend Piercy hath forgot his once-esteemed companion, Walter Tresham? Pie. My worthy Tresham! --my old schoolmate-yes, I trace thee now—thy hand—I’m glad to see thee. Faith, thou art changed indeed,! No longer now the lively boon companion; time has made furrows where erst were dimples on thy cheek. Wal. Oh! ‘tis true time is a busy workman: thee, too. I find much changed since we last parted. Thy eye hath dimmed its lustre, and thy brow hath lost its wonted arch with frowning. What weighty cares have pressed it down? Pie. Cares!—No thought of moment; the mere effect of riper age. But, foregad! I rejoice that we have met again. Where hast thou hidden thyself so long? What mischief hast thou worked? What toils pursued? Wal. Many and various; to thee I’ll tell them o’er; for at thy hands I come to seek some solace for my woes, some counsel to redress them, and some friendly aid to work their cure. Pie. And thou shalt have it—though I am changed from what I used to be, still I have heart and hand to serve my friend: go on-wherein can I aid thee? Wal. ‘Tis now some three years gone, I left my home; doubtless thou knowest the cause.—my marriage with the Earl of Morley’s daughter; I might call it fatal, but that I own it the source of countless joys to me, although it hath been the harbinger of my misforture. Pie. As the old proverb runs-woman is ever at the root of man’s mishap. Wal. ‘Tis but too true: the haughty Earl reviled my lowly birth, and my poor father, stung with proud resentment, alike forbade the match. Against all wishes but our own, we wed, and flew to France where I was blessed to find myself a father. Cheerfully I toiled to supply the loss of patrimony; cut off by my relentless parent’s dying testament, my lovely Eleanor, too, applied her tender frame to honest industry. The morning found us cheerful, the evening contented; till our kind stars were clouded: sickness came, and poverty with gaunt looks stared thorough our humble lattice. ‘ Pie. A dreary guest to lovers, truly. Wal. My little treasure dwindled-my arm of labour weakened-my spirits daily sinking—in a strange land—no friend to comfort or cherish my fond partner and my child, should death assail me-‘twas quickly fixed to give up all, and hasten back to England. Hither we arrived some six days past, and wearily have paced our way from the Kentish coast, in hopes, by the assistance of thy known intimacy with stern Morley and his gay son, the Lord Monteagle, to gain a kind protector for the objects of my love, then die content and sleep amongst my kindred clay. Pie. Thou shalt have my every effort. Wal. ‘Tis kindly said: I knew I could not be deceived in thee, although the world— Pie. (Agitated, and endeavoring to disguises his feelings.) The world’s a liar—sure, it could never whisper evil of me. Wal. They told me thou wert stiff and formal grown, a deep philosopher, secluded from thy friends, and almost misanthrope: turning the night to day, and day to night. For that I sought thee at this early hour that I might win thee ere thy studies or thy whim drove thee from the fair sunshine. Catesby (Within, R.) What, ho! Hugh Piercy, wilt thou leave us here? Pie. (Aside) How shall I contrive his absence? Wal. I find thou art not quite companionless. Pie. Why, no: a friend within awaits me for dispatch of trifling business. Wal. I pray, I do not hinder thee: haste, then, to him,--I will refresh me here, awhile; the toil of my journey and my weak state have need of it. Pie. 'Tis well; (Pointing to an arbour, L.C.) sit thee in yonder arbour that doth o’erhang the river’s margin. I’ll come to thee, anon. ‘ (Bars the gate, L.S.E., and exit, R.S.E. Wal. Yes; I will sit me here and rest awhile, and gaze upon the sun that, blushing, seems to view himself in yonder lucid mirror, I’ll count the waves that chase each other from the broad stream, as man doth tread upon the heel of man, and in the recollection of the happy past forget the painful present and the future. (Retires in the arbour, L.C., and falls asleep.) Enter Master Richard Catesby and Sir Everard Digby from the house, R. S.e. Cat.(C.) What I speak is an unvarnished truth. Dig. (S.C.) ‘Tis certain-we are beset on every hand; the locusts of the court, like the locusts of the wilderness, eat up our goodly fruit and poison even the root and branches. Cat. At every turn a Scotsman meets our eye, as thistles spring to prick us on a common. Dig. In short, without some remedy in public deeds, in private actions, in church as well as state, the land is ruined; and goodly England, so long adorned with conquering laurels, shall sink to be a crouching slave to every upstart foe. Cat. ‘Tis sure as is the grave, unless the efforts of our little band shall stem the current ere the flood comes on. Dig. It must—it shall be so. Shall the free sons of Albion stoop to despot power, bend to a coward, yield their fair honours to deck Scottish sycophants, and owe allegiance to a foreigner?—No. Cat. ‘Tis bravely said; attend me, then, friend Digby: hearken, and let thy ears drink pleasure. This is the summit of our plot—good master Piercy, yonder rents a huge vault beneath the House of Lords; ‘tis well stocked with coals and faggots, a seeming store of fuel for the winter: but know, friend Digby, beneath the pile some six-and-thirty casks of powder are disposed, and ‘tis our purpose, when the coward king shall open Parliament, to put them to a glorious use. Dig. Thou wouldst despatch him! ‘tis spoken nobly. Cat. ‘Twere needless if no more were lost than he; his children would retain with greater vigour the tyrant system. Dig. But by this lesson surely the Parliament would profit. Cat. Yes, to redouble our grievances. Thou dost not freely enter all my views; to set us free, ‘tis necessary we rid ourselves of every enemy; and, by a single spark of fire, the whole—king, royal family, peerage, and Parliament—shall meet together their desert and doom. Dig. Illustrious thought! My heart and soul pant for the execution; but where, alas! Where shall a hand be found possessing nerve enough to strike this blow? More grand, more noble, more terrific, than the fiercest act on which the destiny of nations ever hung. Cat. Fear not, a doughty villain has been found; our colleague, Thomas Winter, hath procured from the low countries an accomplice who shall do the important deed-one Guido Fawkes—a Spaniard by birth, but whose obdurate soul and countless crimes expatriate him from his native soil, and fit him for the direst occupations. Dig. Is he at hand? Cat. Each anxious moment is his coming here expected- (A suppressed note on the bugle is heard.) ha! ‘tis the signal!—see, the barge approaches—‘tis our good friend conducting hither this same valorous Guido Fawkes. ( A barge crosses- Winter mounts the stairs at the back, supposed to lead to the river—he then gives a signal, which is answered. Enter Master Piercy, Rockwood, Grant, and Caies, From the house. R.S.E. Win. Good morrow to all. Cat. Good morrow; welcome to our firm friend, Master Winter. Pie. (Aside.) Where is the unhappy Tresham!—Ha! I see he sleeps—‘tis a most fortunate chance—he will be still a stranger to our dark designs, and ‘scape my comrade’s searching eyes. Win. I have him underneath the garden wall—a man he is most fitting for this work—solid and steady as the rock of adamant; fierce as a burning forest; his countenance the picture of his mind; his heart like to the icy element. I hold it, comrade, a most lucky omen of our final triumph, that the fates have placed so fit an agent in our power, as the redoubled Guido Faux. Have I your common consent to introduce him? Cat. Even so. (Exit Winter down the steps, L.U.E. Re-enter Winter with Guido Faux, up the steps, L.U. E. Faux. (c.) How now, good Master Winter? are these the desperate band thou speakst of?—By our lady, ‘tis a blessing they have me amongst them. There seems not one that hath a heart beyond the courage of a chicken. Win. These are our friends—a valiant few, who prize their liberties beyond their lives. Faux. Life is a play-thing; a mere child’s toy—and men like us do use it for our very sport: If it wins, we treasure it awhile, but ere we win, ‘tis meet we hazard I’ the game. Cat. A goodly and a sage remark. Pie. Nay, prithee, friends, be hush; the day advances, neighbours are afoot—(Aside.) and my poor friend may awake. Dig. Art thou appraised of the mighty task thou has to act? Faux. Fully Dig. Dost think thou hast the energy to fire a train, which, in all human probability, shall hurl thyself to eternity? Faux. Not only myself, good sir, but you, and you, and you, and forty other such, if they are to be found. Cat. A proper instrument to work our hidden mischief. Say, Guido, ere we close with thee, wilt thou conform to all our regulations, and pledge thyself upon the sacred communion of our faith, to keep true fealty to our brotherhood? Faux. What means this jargon of faith and sanctity?—Speak few words and plain. Dig. Wilt thou swear to be true to us, as we have done? Faux. No: cowards are bound by oaths; a brave man’s word is his bond. Cat. Wilt thou promise never to desert our cause? Faux. No; your cause may dwindle to a thing beneath my notice. Roc. (L.) Wilt thou engage to abide a member of our body? Faux. No; it may happen your deeds might disgrace me. Grant. Wilt thou preserve our secrets? Faux. Ay: if all goes right, they will not want long keeping. In short I come far and warily, to join ye in a mighty deed—if your hearts sicken, I will go back—there’s mischief enough in the world to keep the devil and myself in full employment—but, if ye are staunch, there is my hand-and may it wither when its master blushes for its cowardice. Cat. It is enough. Now disperse we, some to the front door, some to the postern gate, while I and Digby take our place in Winter’s barge. Farewell: at midnight we re-assemble. Dig. Farewell—perdition light upon our enemies.

(They embrace, and are about to go off. Wal. (Exclaims in his sleep.) Oh, spare them, spare them! Cat. (Discovering Walter Tresham.) Ha! Who have we here? A listener! We are then at his mercy. (They drag him forward. Pie. Spare him; he is my friend. Cat. He ne’er shall be thy foe. This to his recreant heart. (Goes to stab him,) Faux. (L.C.) Hold, that is my office. Wal. (Kneeling, C.) What means this turmoil?—Am I awake, or dreaming still?—Methought I saw my loved wife and child, writhing beneath the murderer’s grasp. Are ye the monsters?—Tell me, is it true?—Have ye sacrificed them both? Faux. No: ‘tis thy turn first. (Goes to stab him.) Pie. Hold, Hold! He is my valued friend : spare him, if ye have any love for me. Cat. If he be thy friend, he will keep thy secrets. Say, stranger,--- Wal. (Rising.) I know not what ye speak of. I have obtained no secrets: I have courted none. Cat. Art thou an Englishman? Wal. Thanks to my lucky stars, I am. Cat. Dost thou love thy country and its liberty? Wal. As my life, Cat. Wilt thou defend them? Wal. To the uttermost—I have, and will again. Cat. (Crossing, C.) Then swear, by all the powers of heaven and torments of the damned—by thy hopes of mercy and thy fears of suffering—by the sacred ghosts of thy fathers—by the blood of thy innocent offspring—by every tie that binds humanity—swear never to divulge, but be a faithful member of our brotherhood. Wal. It is amazement all! I know not what ye would press me to-ye are all strangers, perhaps deadly foes; (Crossing to Piercy, and taking him by the hand.) but here’s a true and old friend—what says Hugh Piercy? (Aside to Piercy.) Knowest thou these gentlemen? Pie. Well; my sworn brothers— Wal. What is this secret? Pie. To benefit both thee, and me, and all of us. Wal. By honorable means? Pie. Honour will constitute our chief reward. Wal. Enough, enough! I’ll take thy word against the world that all is right, and seek no further explanation. Pie. Give me thy hand; we are true friends, and thou must take the oath. Wal. (Kneeling, C.) I do, I do—I swear, Cat. ‘Tis well: now part we till the midnight hour shall come. Farewell. (Exeunt severally R. and L.) Scene II. The Ante Chamber at Whitehall. Enter Lady Alice and Dame Margaret, L. Mar. (L.C.) There, gang thy ways for a pert, that skippest about, and plumest thysel’ as proudly as ony chitling o’ the feathered tribe. Alice. (c.) To be sure, old nurse and why not?—An’t I young, and free, and well dowered, and withal not illfavoured?—What should musty thought and wrinkled cares have to do with a gossamer creature like me? No, no, Margaret, thou hast enough of wrinkles to frighten every thought out of my poor head, and keep me careless and smooth-faced to the end of time. Mar. Hoot awa wi’ thee! Thou’lt have muckle cares enow in good time; sly Maister Cupid is a pawky chief, and will ruffle your heart, though he maunna wrinkle your pretty face. Alice. Oh, a fig for such cares. Whenever the little god shall, in his great mercy and kindness, take it into his noddle to send me a suitor—and I pray daily he won’t be long about it—if he be good for anything, I shall be as careless as possible, in order to make him constant; for the men are very whimsical creatures; and if he be a worthless fellow, I sha’nt care at all about him. So, you see, I’m not likely to show any wrinkles on that account. But, see! (Looking off, R.) truce to giggling—put on thy sober looks with thy hood, nurse Margaret, and set thy foster-child a staid example. Enter King James, Lord Suffolk , and Lord Salisbury, preceded by Pages, Yeomen &c, R. King. Haud, gentlemen, haud! I spy a glittering star yonder in the dingy horizon, and your true philosopher, when he ha’ gotten a lustrous body in the focus of his gazing-glass will never pass it unconned. Good morrow to my fair ward—how fare you, pretty Alice?—Foregad, I ken, from these twa laughing eyes and that pretty red-rosy cheek, that smoky London has not power to dim thy brightness. Alice. (L.C.) Your majesty is flattering: whatever I possess of light is borrowed from your kindness. I am the pale, cold moon, that ne’er would shine at all, but for the sunny rays of your majesty’s smiling favour. King. Foregad, a pleasant conceit, and well turned. Thank ye, thank ye,--I do remember weel that Horace hath forestalled thee, though, my pretty witling, in an ode beginning-hem-but’tis nae matter, ye ken not the Latin. Come hither, chit. Thou knowest, when my liege, Lord Cameron, thy worthy father, died, for much important service rendered to us, I did engage mysel’ to foster, guardian, and protect his only issue, thy fair self. Alice. Alas! That fatal chance should place me in a state to burden your majesty’s kindness. King. Hoot, hoot! When we do a kind act, foregad it pays us back wi’ interest. Terence says it better-but ye are ignorant o’the classics Weel, list ye: I trust till now I ha’ fulfilled my promise fairly and faithfully: it hath been my grandest ambition to act the feyther to thee: I ha’ given thee lodgment in our royal palaces; I ha’ brought thee here to England, the country of our birthright, and now that ye are come to womanhood, I ha’ hopes to end my task by getting thee a kind and worthy husband. Alice. A husband! I prithee, mention not the odious word. King. Hoot, hoot! Dowse sic maidenish airs. I do expect a worthy Cornish knight to-day, one Sir Tristram-something, who, by the general report, hath muckle siller, and by his own, doth not lack beauty. Alice. Methinks he might have left that to us to find out, though I should not wonder, after all, if it costs all my penetration to discover his boasted qualifications. King. Why, to say truth, he might have been a wi’ bit more delicate of his ain praise; but ‘tis not everybody has that superior wit which we possess, to let the world unravel our perfection. However, chit, though his personal charms may fail, he hath an unfailing purse, a good estate,--ay, and can read the classics. Alice. A very bookworm, I’ll engage: a walking specimen of typography. To think that I must be tied to a musty searcher after ancient dates and treasurer of quaint legends! If I must be tied to a male being, sure there are sparks enough about the court, without this outlandish Cornwall knight troubling himself or me. King. Go to, go to! Art disobedient, Alice? Foregad, I’ll not be contravened. What I have done is for thy good, and thou shalt have him. Get thee to thy privacy; after the levee, I shall bring the worthy knight and introduce him. D’ye mark, madam! Foregad, that obstinate air stirs up my choler, and I could vent the curse of Sophocleus upon thee- but that nobody here understands one word of Greek or Latin. Lead on, my lords. Learn, rebel madam, that we are a free king, and, foregad, we will be obeyed. (Exit King James and Attendants, C.D.F.-The Yeomen of the Guard remain near the door. Ali. Nurse Margaret, ought I to cry at my good guardian’s displeasure, or laugh at his folly? Ha! Ha! You see nature will prevail-ha! Ha! Yes, yes—if this learned lover should have his way, I suppose he’ll stick me on a shelf in his library, among his lexicons, for occasional reference. But, egad! When we’re married, I’ll show him, if I have but little learning, I have plenty of spirit—I’ll burn every rival book that comes in my way, and leave him no other volume to peruse-but myself. (Exit, R.) Mar. Ha! Ha! She kens weel what influence she has wi’ his royal majesty. O, she’s a merry one, and though she worry his grace a little, yet, forsooth, will she soon spy the road to win him back again. (Going, R.) Enter Lord Monteagle, L. Mon. (C.) Hist, my good dame—saw I not the Lady Alice here but now? Mar. (R.) Troth, your lordship might if ye had put your eyne to test, for she ha’ this moment quitted. Mon. I hope she took no ill from her last night’s walk on the terrace. Mar. She took nothing worse than your grace administered; for she grew directly melancholic, and went to bed supperless. Mon. I grieve to hear it. Bear her my best of compliments, and say I hope to visit her anon. Be thou my friend, and for thy guerdon here is the king’s picture. (Gives money. Mar. By my faith, too, set in gold! Ah, I see your lordship kens the way to a lady’s heart. I’ll not fail thee. A Jacobus, as I live. (Exit, R. Mon. Pretty Alice! If thou wentest to bed supperless, there was one kept thee company, and remained sleepless when he got there. Her lovely image floats before my eyes, like to some fairy vision on a summer eve. But so, the court is begun: I must in, and try by my attentions to the king to win his ward. (He advances to the door, C.f., and is stopped by the Yeomen of the Guard Mon. How now, sirrahs? Yeo. My lord, you cannot pass. Mon. Not pass? Knowest thou who I am, fellow? Yeo. Yes, the Lord Monteagle. Mon. Well, fellow, thou knowest his majesty hath granted me his special entrée to the presence. Yeo. That was yesterday, my lord. Mon. I thank thee, friend: I had forgotten how great a change is worked at court by one poor circuit of the dial. Rules are formed and broken here, as quick as pie-crusts at a pastry-cook’s. ‘Twas but yesterday I had a two-hours gossip with the sapient monarch. A plentiful quantum, to be sure, to last me for a month—and it seems his ministers are of the same opinion, for they cut me short of further indulgence. Well, I suppose I have some good friend among them, who either thinks I owe him more attention, or that the king has paid him less. Let them indulge their humour: the day may come, when they shall pay court to me; and, till then, I’ll hie me home to Southwark-live among my friends, since my foes won’t let me live with them—grow merry for very disappointment- get lusty from extreme sorrow-become respected in spite of myself—and, being less a courtier, die a better man. Enter Sir Tristram Collywobble, L. Mon. Who have we here? Some worthy, destined to be my successor in the galaxy of favor. A good morrow, friend—I am your grace’s servant. Sir. T. Good morrow to thee, friend, and well met. If thou wouldst be servant unto me, I pray thee show me in the presence, for I am strange at court. Mon. Egad! Thou art strange enough any where. Sir T. And I am to salute the king to-day. Mon. Do it carefully, then, for his majesty bears a rough beard, and uses a blunt razor. Pray, friend, art thou an aspirant to the woolsack? Dost thou expect to drain the Tweed? Or has thy grandam prognosticated thou wouldst bring down the stars, to make street lanterns of? Sir T. No, no: I am Sir Tristram Collywobble, of Gander Hall, in the county of Cornwall, Knight, a bachelor of arts, and justice of the peace. Mon. If Justice’s robe were of my choosing, thou hadst never been of the piece, I can tell thee. Adieu. (Going, L.) I pray your bachelorship go home from court with no more arts than thou hast brought from the university. Sir T. Nay, do not leave me without the information I desired. Mon. What wouldst thou? Yonder is the court. Sir T. But tell me, friend, for I perceive thou art initiated, what course must I pursue? I am to have his majesty’s special favour; I am to have promotion , a seat in Parliament, and a wife. Yes, I’m to espouse the Lady Alice, ward of his majesty. Mon. (Aside.) Not if I can help it, Sir Tristram. Oh, that I should live to hear this! My lovely Alice wedded to this perpendicular gander- confusion! Sir T. My Lord Salisbury, who is under obligation to the power and wisdom of our family, has promised me all this; so, thou dost observe, I have enough to do, Heigho! Tell me, then, the customs. Mon. Well, then, thou shat take this for thy manual: the king is a good plain sort of man, who asks no great humility from any one; but he that desires to push his suit at court, must learn to bow deeply to the minister—to flatter the favorite—to change opinions with every wind that blows—and swear the present is a lasting creed; he must be arrogant to inferiors—he must be abject to his equals—and he must suffer the upper rank to clean their sues upon his doublet; he must find wit in empty heads- beauty in vice and ugliness; he must swear big oaths- tell a lie with a good grace-sigh at other’s joy, and laugh at other’s woe; he must fawn, flatter, cringe, and swagger, and do as much dirty work as a scavenger would rate at tenpence a day. This, most wise Sir Tristram Collywobble, of Gander Hall, is the art of a courtier. So, fare thee well, and profit by my lesson. (Exit L. Sir T. Heigho! If all this be needful, ‘twill take a month of Saturdays to give me preparation. Why, it costs more toil to become a courtier than to gain a degree at Oxford, to get upon the quorum, to fish, hunt, hawk, play quarter-staff, and drink strong ale; and yet these elegant accomplishments have cost me two-and-twenty years study. Oh! Tristram Collywobble, if there were not a fair lady in the case, thou surely must dispair; but here goes—since I must bow to the great, here be a couple of rare big ones. Gentlemen, your servant-accept the gratulations of Sir Tristram Collywobble. (He Bows to the Yeomen, and exit, C.D.F. Scene III- The Gate and Court-yard of Monteagle House. Enter Walter Tresham, agitated, at the gate, C. Wal. What have I done, and whither shall I fly to hide my misery, and chase my terror? To think that I, who erst would shudder if my foot had crushed a worm, should now concur to shed the noblest blood of all the land; and, mid the rest, the brother of my treasured Eleanor! Oh, horror! Horror! Grant me but power to warn him of his danger to do the utmost that my oath allows; then, just heaven! Launch an unerring thunderbolt, and strike me into atoms. Here is Monteagle House, where oft, in happier hours, Monteagle and myself laughed care away.. How changed the times! Behold me now, wretched, on the threshold—while he securely dwells within, nor heeds the coming tempest. Now, Walter Tresham, nerve thy courage up—knock at the door thou has been spurned from, and render good for evil. (Knocks at the door, R.S. E. Geo. (Opening the door and looking out.) How, now--who knocks? Wal. Is thy good lord within? Geo. No. Wal. Dost thou expect him? Geo. Yes. Wal. At what hour? Geo. I know not. My lord does not consult me, concerning the hours he keep. Away, fellow. (Going. Wal. Nay, prithee, friend, a moment— Geo. A short one, then, for I have better business. Wal. May I crave of thee a favour? A trifle for thee to do, though dear to me. Geo. Dost thou take me for an equal? Fellow, get thee hence! Wal. Nay, it concerns thy lord, the Lord Monteagle. Wilt thou deliver to him— Geo. He hath no time to waste on thy beggarly memorials; nor I to throw away in attempting to convince thee so. Good night. (Shuts the door loud. Wal. Ha! Wretch that I am! This menial slave, that once would lick my foot now views the marks that villany depicts upon my face, and scorns to parley with me. Unhappy Tresham! Was it not enough to bear the scoff of pride, the stings of fate, the frowns of fortune, and the weight of care; but thou must league, perforce, with traitors, murderers, fiends, to do a deed—but, hark! Footsteps approach-‘Tis he, ‘ tis he! Perish all adverser feeling-revenge for wrongs is sweet; but to forgive and save, are Heaven’s own attributes. Enter Monteagle, L. Mon. Pestilence! To think that I should be so treated. I see the cause plain enough: Salisbury has found out the attentions I have paid to the fair Alice (for in a palace the very walls have eyes and ears), and fears lest I should supersede his Cornish protégé; but this shall not impede me: if I find she loves me, by my honour, I’ll espouse her, though all the kings and courtiers in the world object! Ay, or the Usher of the Black Rod himself should stare me in the face. (Goes to knock at the door-Tresham stops him. Wal. Hold! Mon. Who art thou? Dost presume to impede me on my own premises? Wal. A friend. Mon. Not a very cordial one. Thy business? Wal. Thy welfare. Mon. Disinterested, though mysterious. Wal. Take this. (Gives a letter. Mon. I hope it augurs me no ill. Wal. The reverse, if thou wilt profit by it. Mon. If there be any to be gotten by it, I will use my best wit to find it out, and, to that end, will take the clear of the morning for its perusal. Thank thee: good night. (knocks at the door.) What, ho! A taper. (Exit into the house, R.S.E. Wal. Ha! The morning! ‘twill be, perhaps, too late. What’s to be done? How to shake off his safe indifference? I’ll knock again, and tell him all I know—yet, oh! The sickening thought, my oath, my oath! Propitious heaven, direct me! Mon. (Within.) Follow me to the court-yard, instantly. Wal. Ha! He comes again, and with the letter. I have succeeded, then, and all is well. (Exit, C.F.

Re-enter Mounteagle from the house, R. S. E., followed by Geoffry and Nicholas, with a taper. Mon. Pray, my good friend, where gottest thou this idle scrawl?-Ha! Gone! Vanished! A most mysterious action, truly. Geoffry, sawest thou that muffled knave? Geo. My lord, he left the court but now. By the pale moonlight, I discern him yonder, posting with hasty step towards the end o’ the street. Mon. Follow, my trusty Geoffry, with the utmost speed, and, as you value me, bring the knave here again-there’s treason afloat. Geo. Whate’er a willing heart and a light heel can accomplish, thou mayst expect of me. (Exit, C.F. Mon. Away, away. ‘Tis strange—I’ll read it o’er again. (Reads) "My lord,--Out of the love I bear your family, I would advise you to shift off your attendance at Parliament to-morrow; for God and man have concurred to punish the wickedness of the time—there shall be struck a terrible blow, and none shall see who hurts them. Contemn not this counsel, because it may do you good, and can do you no harm, for the danger is past as soon as you have burnt this letter. May God give you grace to make good use of it!" No name—no date—‘tis wondrous strange! Let me in, and ponder o’er it well. Sure, there’s some dark intent, that this should bring to day. Kind stars, direct me to the fatal truth! (Exit into the house, R. S. E., followed by Nicholas. Scene IV.-Tresham’s lodging-a truckle-bed in one corner, and shabby furniture; a lamp nearly extinguished-A Storm. Eleanor discovered watching her sleeping child. Ele. Roar on, ye winds! And still, thou pitiless rain, beat rudely ‘gainst yon tattered casement: such sounds are suited to my melancholy, and will prove a fitting lullaby for this wretched babe. Ha! That sigh! Poor little innocent, thou canst keep me company in sadness-a kindred grief pervades thy unsuspecting breast in sympathy with mine. Oh, Walter! My beloved-my cherished-my almost adored-why hast thou brought me here in fond expectancy, to dash my hopes so soon, and drive me to despair? Why dost thou linger, since the break of morn till now, the midnight hour, from thy so oft-acknoweledged haven, my dejected breast? Why hast thou left thy wife, thy home, thy babe? Oh, ye indulgent powers of good! Direct him safely to my arms, or let the same shaft pierce us all together. Ha! A footstep-he comes-my heart leaps up, and scarcely keeps its bounds. Enter Walter Tresham, In disorder-he bolts the door hastily. Ele. My love! My lord! My husband! (Falls into his arms.) Oh! I am bless’d to press thee once again—yet, ah! That look- What ails thee, Walter? Wal. (Fixing his eyes steadily on her.) We are undone, and the malice of hell hath overwhelmed us. Ele. Just heaven! What do I hear? Wal. Dost hear him? Is he then at hand? Ele. Who dost thou mean? All is silent-‘tis midnight-heavens! What an altered face!—See, too, his rolling eye—his quivering lip. What is thy grief? Speak, I conjure thee. Wal. Nothing- nothing. Ele. Then why this change? Wal. Eh!—What? I know no change. Ele. Tell me, what sudden illness doth o’ercome thee? Thy countenance is— Wal. Ha!—my countenance-is there, then— Ele. ‘Tis pale and ghastly. Wal. Ha!—‘tis mere fatigue and weakness. Ele. Thou dost need repose, my husband. Wal. I do, indeed, and with thy care shall soon revive again. Where is my boy? Ele. See, he sleeps—I will bring him to thee-his waking smile shall cheer thy heavy heart. Wal. Not for the world! The sleep of infancy is far too calm and innocent, to sacrifice for idle causes— Would that I might sleep as sound as he!—(A noise heard without,) Ha! ‘tis certain, then , he comes. Oh, if thou hast a throb of love remaining, protect, conceal me! Heard ye that noise? I am pursued! He comes!—he comes! The hunter has found out my hiding-place, and death and infamy await me! Ele. What means this frenzy? Wal. ‘Tis truth!—hide me –oh! Screen me from his grasp, and our sweet babe’s first accent shall be to bless thee! (Footsteps are heard-Eleanour hides him behind the hangings of the bed in the flat, L. Enter Geofry, L. D. Ele. (C.) How, now, stranger? Geo. (L.C.) Pointing his sword,) Stir one step, and death shall be the forfeit of thy temerity. Ele. What is thy purpose? Geo. I am in pursuit of a traitor—I have traced him to this wretched house—I saw him enter as I turned the corner of the street, and I will have him. (Searches about . Ele. Bravely spoken—and thinkest thou a poor defenseless woman has the power or inclination to succour treason? Look on me—know my sex-and henceforth learn to be more mannerly. Geo. Hast thou not a husband? Ele. Yes-far beyond thy reach. Geo. Why wert thou out of bed at this late hour?

Ele. The shrieking infant doth demand its mother’s watchful cares. Geo. Hath no one entered in the last few minutes? Ele. None, but the present company. Geo. (Aside.) Her steady firmness quite confounds me, (Crossing towards the bed.) Yet, say, is there no inmate of this building who holds a suspicious character? Ele. The guiltless are without suspicion; therefore, know I none suspected. Geo. I must have been deceived-guilt cannot harbour here with frankness such as this. Woman, farewell. I crave thy pardon for my error. Ele. Thou hast it. Good night to thee, and safe return. Exit Geoffry, L.D. Wal. (Coming slowly forward.) I am then safe, once more. Bless thee! Bless thee!-Ha, ha, ha! (Bursts into an hysterical laugh, and sinks into Eleanor’s arms.—The curtain slowly descends. End of Act I. Act II. Scene I.—King James’s Study—a table with books, paper, pens, ink &c. King James seated at the table , C. reading a letter-Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, attending. King. Aweel, aweel; the mair I ponder on this mysterious

billet, the mair am I bewildered; ‘tis like the riddle of Oedipus: hem-but

ye ken not the Grecian, I believe- (Reads.)—"A terrible blow, and

none shall see who hurts them. " That indicates some hidden conspiracy;

some effusion of gunpowder, or commotion of steel: foregad! ‘tis no such

enviable post to be a king, if one is doomed to such a fate as this—however,

’tis loyal and attentive in the young lord to make so speedy a communication;

we are thereby enabled to make diligent search, and must leave to heaven

the rest.

Cecil. Take my word, sire, when my Lord Suffolk returns from searching the Parliament House and its purlieus, your majesty will own me right; and see, to dispel all doubt, the chamberlain approaches. Enter the Earl of Suffolk and Lord Monteagle, L. King. Ye are welcome back, my lieges; and, foregad, the sight of ye is pleasant, if it be but to abridge suspense. Ha’ ye taken them prisoners? Ha’ ye discovered the ammunition, and removed the arms?—Speak! Have ye searched the adjoining chambers, and the vaults beneath?—Saw ye no suspicious lurkers onywhere? Earl S. We have examined high and low, the roof, the walls, the cellars, and every individual on the premises; but all is safe. Cecil. What says your majesty? Was I not right? King. Why, e’en as Statius says—hem-but that’s no matte; although I favoured the search, I felt a certain consciousness of security; my courage was unabated. Why stands my Lord Monteagle silent? What says he to this notable discovery-this writing-paper plot? Mon. He’s glad to find his king is out of danger. King. Weel, that is brawly said. And art thou sure? Is thy mind content that there is no conspiracy? Mon. None, that I could discover, even with assistance of the chamberlain—and courtiers are said to have keen eyes—unless, indeed, we are to be alarmed at a conspiracy of rats, who, for mere want of use, have gnawed some divers holes in the hangings of the throne. The Parliament House hath been long infested with such vermin. Cecil. Ye saw no arms? Mon. Oh, yes! The king’s arms at the throne back, but no other. King. Ye found no combustibles? Mon. Plenty in my friend Master Piercy’s cellar; there is enough to furnish his hospitable kitchen-fire for the whole winter. In short, my liege, I do confess the letter an indissouluble mystery, and my errand here entirely superflous. It pleasures me to find it so, although ‘twill furnish some folks with a rich theme for ridicule for months to come. Cecil (Aside, to the King.) My sire! Observe, he winces, My life on’t ‘tis a bubble of his own blowing. King. (Rising) It doth appear so. Ay, ay, my dainty lord, we are no nestlings to be caught wi’ chaff: thou dost seem merry? Mon. I have good cause:the danger’s o’er. King. Hoot, hoot! ‘tis plain enough ye ha’ played us this trick to divulge your mother-wit; but awa’ wi’ ye, and learn to whet your humour on some fitter stane; your idle tale we laugh to scorn. Ha, ha! As Seneca says, hem-but we waste breath: ‘tis a good moral thrown away. Mon. Nay, good my liege, I protest your majesty is in error. King. ‘Tis the first time, then, and I’ll nae be reproved by a stripling sic as thee. Get home, and study your classics; ‘tis better amusement than attempting to shake the nerves o’ your lawful sovereign; d’ye hear? We are a free king, and, foregad! We will not be trifled with. (Exeunt all but Lord Monteagle, R. Mon. Wheugh! Here’s gratitude for a sleepless night, and four hours’ occupation before breakfast: well, if ever I meddle in state affairs again, may the devil, who presides over mischief-making, blister my feet, and send me on a journey with tight buskins. (Exit, L.) Scene II. –Tresham’s Lodging-table, chairs, C, as before. Tresham discovered asleep on the bed, L.C.F., Eleanor sitting near, watching him. Ele. At length he sleeps; hushed be each passing breeze, and every ruder noise be mute, while his disturbed faculties are lulled to sweet repose: how my heart bleeds for him! Excess of toil, weak state, and perhaps some rude encounter he hath met in efforts to awaken my gay brother’s love, seem to have shook his reason. That rude pursuer, too—he spoke of crimes; but perish the vile thought; my Tresham’s heart is of a bland and open character, and sure, he is the victim of some vile mistake. Oh, what a night hath passed of grief and horror! Heaven, in thy mercy, spare us such another. Wal. (In his sleep.) O, Monteagle! Hear me! Ele. ‘Tis as I said; my brother hath opposed him, even in his dreams he cannot bear the contumely-and this for me, too! Oh! Why was I ever born? Wal. Ha! It burns-it bursts-it blazes- they scream-they sue for pity: pity has naught to do with souls like ours; they sink to the abyss: hark, how their bones now crackle in the blaze! See how their blistering flesh doth feed the fire! Heard, ye that groan? The expiring sigh of fifty worthy hearts! (Wakes, rises, and pushes forward.) Unhand me-let me go-I am not guilty: spare me, for my loved Eleanor! Ele. (Rising, and supporting him.) Walter, I am near thee- fear naught-‘tis but a dream. Thy Eleanor is here. Wal. A dream? ‘tis reality. Saw ye not their agony? Oh! ‘tis impossible to bear the stings of such a conscience? Ele. Nay, prithee, Walter, let me share thy grief-tell me all; I will console thy troubles-administer relief. Wal. I have sworn never to divulge: ‘tis the first secret I have locked from thee since thou didst share my heart—pardon, it will be the last. Ele. (Taking his arm firmly.) Walter Tresham I can be firm as well as thee: administer thy oath—I will not falter. Wal. Forbear, forbear; the truth will reach thee soon from other lips. (Running to the table and snatching up a pistol.) ‘Tis fixed—farewell for ever. (Places the pistol to his head- Eleanor snatches her child from the bed, and holds it to him-he melts into tears, and drops the pistol. Ele. (Screaming.) Mercy! Mercy! Oh! Wal. Just God. forgive the impious act! My loved wife-my little one—that tear, and those sweet artless smiles, strike to my fevered soul, and call me back to reason. Oh! I have suffered deeply; but kind Providence will surely pardon and restore. Ele. If thou art guilty, as I think thee not, live then and repent. If thou hast injured friend or foe, bestow thy life in making reparation. Wal. Thy words are balm—a beam of heavenly light to guide my way. (A bugle sounds without.) Ha! ‘tis the signal-I must away. Dear faithful partner, thy monishment hath sunk to my heart’s core; believe me, I shall cherish it. Pride of thy father’s heart, adieu! (Kisses the child-Eleanor detains him-he breaks away.) Nay, thou must unhand me. (The bugle heard again.) The time is come, and I must obey my oath. (Struggles and exit, L.D. Ele. I cannot solve this mystery: but with my utmost woman’s courage I’ll pursue his steps, and be his savior, or perish with him. (Exit after him, L. D.) Scene III. –Ante-Chamber in the Palace, Enter Lord Monteagle, L. Mon. Well , spite of his majesty’s threats and my own resolves, I cannot leave this spot. Was ever poor devil in so piteous a plight! My intentions misconstrued-my loyalty suspected—my hopes frustrated—and my love for the fair Alice untold. Nothing remains for me but to creep into some mouse-hole retirement, brood on my misfortunes, grow misanthrope, and forget the insult, the lady, and the letter altogether. Yes, I vow I’ll never trouble myself again about either; although I still must feel some lurking presentiment of evil—a kind of inward monitor, that strikes on my heart, and whispers in my ear, with solemn note— Enter sir Tristram Collywobble, L. Sir T. (L.) Oh, sweet Lady Alice! Mon. (C) The plague on thee! Another devil, in the person of Sir Tristram Collywobble, comes to torment and harass me. Avaunt! Sir T. Nay, good your grace; be not severe, for I am passing melancholic; I’ve seen her-I’ve looked at her –I’ve gazed upon her—and I pine in secret for her. Heigho! Mon. If thou shouldst pine thyself to a periwinkle, ‘twere the better , for then thou wouldst be picked out with a pin instead of a poniard; and death will certainly be thy lot, if thou dost persist in loving her. Sir T. Heigho! Sweet Lady Alice! Must I then give up the ghost? Alas! Dost think, if I should die for love, she would follow me to the grave? Mon. That I may promise thee: (Aside) ay, and with a merry heart, too, or I’m mistaken. Sir T. ‘Tis a consoling consideration, and will make the dust press lighter on my coffin-lid. Heigho! Sweet Lady Alice. If she doth smile upon me, I shall be the happiest of mortals; and if she frown, I’ll die and be a comfortable corpse. Yes, I will seek the maid—throw myself at her feet—look unutterable things- and tell her—heigho! Mon. (aside.) Poor idiot! He has not, then, broken the ice of his passion to her. What a flood will there be when the thaw comes! Sir T. Good your grace, excuse me; I have profited by thy counsel at the court. Wilt thou lend me thy aid with the lady? His majesty hath appointed me an interview with her, alone, this morning, and—heigho! I am so melancholic, I scarce know how I shall deport myself. Pray befriend me in my need. Mon. (Laughing.) Ha. Ha: (Aside.) a quaint conceit, and may be profitable to me. I’ll humour it. Why, true, Sir Collywobble, we dashers of the town are more expert than country honesty at such game. Ye shoot, and hawk, and fish-we practice the art of lady killing; and, by my faith, I have been over head and ears in love ever since I was in breches. Sir T. Heigho! How couldst thou exist? I have been smitten but a good twelve hours, and I am dwindled to a mushroom. Heigho! Mon. Droop not- vanity and high feeding do wonders in these cases. But see, the fair one comes. Adieu. (Going. Sir T. Nay, good my lord; prithee, do not leave me; think of my predicament. Heigho! Stay and say a civil thing or two in the court way for me, or I shall die before my time. Mon. A fine dilemma, i’faith! But I will do thy service. Now, that I had some brazen divinity to invoke for aid! Enter Lady Alice, R. Mon. Fair lady, by your leave- (Takes her hand.) Now, by my honour, thy charms to-day appear so blooming bright, I could extol them to the skies, but that I fear the sun himself, at hearing it, might grow envious, and put the world in darkness ere noontide. Sir T. (Aside.) (L.) How well he doth it! Heigho! Ali. (R.) Ha! The Lord Monteagle! I had not expected the pleasure of this interview. Mon. (C.) Be not surprised, fair lady-‘tis an unthankful world, and I have found it so; yet do I pursue the obliging path , and for the respect I owe Sir Tristram here, and the more chaste regard I bear your ladyship, behold I undertake the task of suitor for him, and trust my words will have due weight with thee. Sir T. (Aside.) Perfection to a tittle! Alice. Upon my word, a pretty office ye have undertaken! So, then, I am to be courted as kings court their consorts, by proxy. Mon. Even so, most charming lady. I am Sir Cupid’s plenipotentiary and chief ambassador; and supremely shall I be ennobled if my suit prevail. Sir T. (Whispering Monteagle.) Now, my good friend, say something about me; do, now—something pretty. Mon. (To Sir Tristram.) Trust me, I will. (To Lady Alice.) Yes , lovely charmer of every eye, and captivator of every heart, all that I have yet said is but the exordium of my credentials and spoken in my own proper person; but now I throw myself upon the earth before thee, and breathe the red- hot passion of my friend, (Kneeling and looking to Sir Tristram.) How shall I begin? Sir T. (Kneeling.) Heigho! Mon. (Repeating after him.) Heigho! Alice. (R.C.) Heigho, again! Mon. (C.) What shall I say now? Sir. T. (L.C.) Sweet Lady Alice. Mon. Sweet Lady Alice! Alice. And sweet Sir Tristram Collywobble!

Sir T. Nay, go on. Mon. Nay, go on. Alice. ‘Tis thou shouldst go on; and, believe me, I am impatient for thy speech. Mon. Then, oh most lovely, chaste, and adorable fair! Know that I love thee more than zephyr loves the rose; truer than needle loves the north; more fervently than Indian loves the sun-—‘tis not an idle passion prompts this declaration-‘tis an ecstatic sparkle from thine eye hath darted to my soul, and marked thee there for ever. Sir T. All that is said in my proper person, sweet Lady Alice. Heigho! Alice. (Aside.) I am bewildered! What am I to think

of this?

Mon. Through many a silent night and gloomy day my sweetest thoughts have been of thee. Months have rolled on unheeded when thou wert far away; for what is life, despoiled of those we love? Sir T. That’s not correct- no months. Phoo! Phoo! ‘tis but since yesternight, Sweet Lady Alice. Mon. Oh, cast one look of pity on me. Sir T. No, no, on me, sweet Lady Alice. Mon. Say but that I may hope, and I will not despair. Alice. (Aside.) My heart misgives me! My lord, I know not if I ought to take this as a sally of thy wonted humour, or as a faithful picture of thy heart. Sir T. True, by my honour, and my hopes of promotion at court. Mon. True, by my honour, and my hopes to merit your ladyship’s favour. What token wilt thou give that I have not o’erstepp’d it. Alice. Thou hast my hand. Mon. Then thus with rapture I pledge my future life to thee, and seal my destiny with a fervent kiss. Sir T. Stop, Stop! That should be me, you know—I am the real sufferer. Heigho! Mon. I have the real happiness! Come, let us away to Parliament: his majesty hath engaged to be upon the throne at noon, and by my count it is not many minutes short. Dear, charming Lady Alice, though fate has hung a dubious cloud about us, the sun of love shall soon break through, and radiate all around—adieu!—Come, Sir Tristram; I’ll school thee as we go, and for a hand to practice on, here’s mine. Sir T. Heigho! Sweet Lady Alice. (Exeunt Monteagle, pushing Sir Tristram off, L.) Alice. Here’s an event! The pretended swain cajoled, and the real lover avowed. (laughing.) Ha, Ha! What will his wise majesty say to this? (Laughing.) Ha, ha! Why, if nature had rained men, the drop I should have selected out of the whole shower would have been this same merry lord. Gallant and gay-a portly person and a lively manner. Oh, he’s the husband for me; and, in spite of the king’s frowns and the dangers of my path, if he will have me, egad! he shall—and a fig for the Cornish knight and his musty manuscripts. (Exit, R.) Scene IV.- Outside of the house of Lords, and the entry to Piercy’s cellar underneath Enter Catesby, Guido Faux, Caies, and Rockwood, From the vault, L.F. Caies. (L.C.) Thou art assured that all is now prepared? Faux. (C.) Complete, save the last office. Cat. (R.) Screw up thy courage to perform that office, and deserve the admiration of the latest times. Faux. I heed not praise, I dread not infamy; and for this piece of work—fear not-if they be not every one destroyed, the gunpowder must be worse than my inclination. Now, fare thee well. Cat. Farewell. Remember, when St. Peter’s bell tolls twelve, the king sits then upon the throne-at the last stroke--- Faux. The deed shall be accomplished. Farewell, (Exit into the vault, L.F. Cat. Speed thy good task, and heaven by thy reward. Roc. Now close the doors, and hasten to our brethren. Cat. Hold! They are so often open, that suspicion may arise if now we shut them. See, our comrades are here. Enter Master Hugh Piercy and Walter Tresham l., and Sir Everard Digby, R., meeting. Pie. Well met-the king will reach the throne precisely at the hour of twelve. Dig. It draws to hand –‘tis a good hour-the midday sun shall light the path to glory. (Drums and trumpets are heard at a great distance, and continue through the remainder of the scene, being supposed to accompany the royal procession. Enter Master Robert Winter, R. Win. Why waste ye time?—The king is on his way, with the proud queen, the Prince of Wales, and all the court attendants. ‘Tis meet ye also know the young prince remains at the palace, and the Princess Elizabeth is at the mansion of Lord Harrington. Cat. To thee, Piercy, who hast the privilege of the palace, we do confide the younger prince—strike when thou dost hearken the explosion; and for the princess— Dig. Leave her to me-Harrington owns me for a friend, and I will use him for my purpose. Enter Grant, L. Cat. How now-this haste— Grant. I come from the rooms above,--the peers and Parliament are all assembled—many of their wives and families, too, are joined, to make a gracious sight: at twelve the king will reach his place. Dig. There are some ten minutes yet to pass- each hasten to his post, and list to the thundering note that gives a nation freedom. Cat. Tresham, for further security, descend to our great champion, and bid him, if he hear a note upon the horn, to stay his hand—if not, the last stroke of twelve is the glorious signal. Away, away; each gallant heart now pants for vengeance. (Exeunt severally, R.-Walter Tresham into the vault, L.F. Enter Sir Tristram Collywobble, with two Serving-Men and Page, and Lord Monteagle, also attended, L. Sir T. By mine honour, a most flustracious day is this to me---what with the presentation, the Parliament, and sweet Lady Alice-Heigho! It shall be an era in the records of our house. Mon. Away, away! No longer idle prate—see, the king approaaches. Thy post in the procession is an earlier one than mine-hie thee to it- I will but tarry here to save me from the idle throng-we shall meet within. Sir. T. I thank thy knowledge in these matters. What should I have done without thee? And what would the sweet Lady Alice do without me? Heigho! Adieu, Sirrahs, step on, and clear the way. Heigho! (Exit, pompously, with his Men, R.) Mon. Heigho! By my faith, I have caught the infection of the soft Sir Tristram. I know not how it is, but an unusual gloom oppresses me-yet hence with vain qualms—see, the procession moves into the house: I must brush off this lethargy, and hasten to my post. (Going. Enter Walter Tresham, from the vault, L.F. Wal. Hold! Mon. Ha! Sure thou art the man I saw last night!

What is thy purpose?

Wal. To warn thee, once more, ere ‘tis too late. Mon. What is thy hidden meaning, friend?—Speak out. Wal. There is no time for parley—get to thy house, if thou wouldst live. Mon. Mysterious man! (Seizing him.) I must know more. Wal. (Struggling.) Nay, prithee, sir, unhand me: I would save thy life: do not forfeit mine. (Breaks from him, and exit, L. Mon. Amazement! How shall I decide? To turn me homeward, or to tempt my fate! Geoffry, thou saw’st that stranger: was’t not the same that crossed me yesternight? Geo. My lord, I do believe it was. Mon. Saw you from whence he came? Geo. From yonder vault, my lord. Mon. Ha! ‘tis Piercy’s vault. A thousand thoughts rush to my whirling brain. Yes, I will enter it once more, and dare to meet the worst. Boy, take my cloak; follow your master, my good fellows; be steady, firm, and silent as the grave. (Exeunt hastily into the vault, L. P. Scene V.-The Vault, apparently filled with faggots. Guido Faux discovered with a lighted lantern. Faux. Yes, I will do this mighty deed as doth become a true Spaniard. (He throws down the faggots and discovers thirty-six barrels of gunpowder.) The blood that boils within my veins, owes consanguinity with many a noble drop spilt by the tyrant junto now within my power. I have despatched full many a wretch to t’other world, in mere cold blood; and shall I wince now, when I may at once revenge my friends, and expiate my crimes? No-I’ll do it bravely, and leave a name of terror that shall frighten age and childhood, and raise the wonder of the world. (Lays a train.) Ha! I hear footsteps-gods of revenge and horror! I call on ye to avert all interruption. Mon. (without.) What, ho! Who is there with a light? (Guido Faux darkens his lantern, and retreats to the back of the vault.) Ha! ‘tis gone! And I am in a labyrinth untraceable! Enter Lord Monteagle, down the steps, R. Mon. Where shall I bend my steps? (Gropes across and exit, L. Faux. (Coming forward. ) Thou shall not again retrace them if I have fortune on my side. (The clock begins to strike.) Ha! The twelfth hour-no previous signal! Then all is as it should be. Geo. (Without, R.) My lord! My lord! Where art thou?—This way-help!help! Faux. (R.) Tis too late! Eleven!-twelve. (Just at the twelfth stroke of the bell, he lights the train.) Now, then, for lasting glory. Re-enter Lord Monteagle, hastily, L. Mon. Monster, forbear! (Sweeps away a part of the train with his hat, and cuts off the communication- struggle. Enter Geoffry, and the other Servants of Lord Monteagle, down the steps, R.-The Page calls for help. Enter Soldiers-they seize Guido Faux-a picture is formed and the curtain falls. End of Act II. Act III Scene I.- Rosamond’s Pond in St. James’s Park, and distant view of Westminster Abbey. Enter Lord Monteagle, L., with Sir Tristram Collywobble, drunk. Sir. T. (Singing, dolefully.) Come, let us dance, and let us sing, Tol lo de rol de riddle; God bless the church, and bless the king, And save us from the Scotch fiddle.

Is this St. James’s Park?—and dost think she’ll come—the sweet Lady Alice?—by my credit, an’ she do, I think I shall have courage to say a few words in the court style to her. Heigho! Mon. (L.C.) A ha, the Canary wine hath made a man of thee, my worthy boon companion; but, prithee, at what hour dost thou expect the fair damsel? Sir T. Why, at no hour, but at the half-hour after two of the clock. Here’s her sweet delicious, elegant polite note—"To the fair knight, Sir Tristram Collywobble, &c., &c."—Zooks! What though the three bottles of Canary I have taken may have maade me a man of courage, they have not made me a man of discernment, for by my credit, I can’t read a single word correctly. Mon. I know not how thou shouldst, worthy Hector, unless thou wouldst stand upon thy head-for, see, the letters are upside down. Let me peruse it. (Reads.) "Chaste Sir Tristram, thus I greet Thy qualities, in accents meet— All the vows I’ve heard to-day To my heart have found their way; Therefore, if thou’rt free from evil, And would fain be passing civil, In the park, at half-past two, Post thyself—to time be true— Near the margin of a pond Folks christen from fair Rosamond; And, in a mask, and mantle fair, Thou’lt meet thy faithful Alice there. P.S. Thy friend should see what I indite, In hopes he’ll riddle it all right- Direct thy steps, and not complain To act the lover o’er again. I see it plain enough—she hath taken the bait, and the effervescence of her with hath devised a plan to bless my longing eyes, and point the road to happiness-ten thousand thanks to her! (Kisses the letter, Sir. T. Ah! I suppose I ought to say that-ten thousand thanks. (Snatches the letter, and kisses it.) But, I say, an’t please your grace, I think I can be a match for her this afternoon. I have gotten a power of compliments by heart. If I can but find words to talk ‘em in. Sweet Lady Alice— Mon. Phoo! I must stand at thy back to prompt thee, and be ready to take up the thread of thy discourse when thou dost fail. (Aside.) Ay and the lady, too, or I’m a conjurer. Sir. T. Excuse me-thou knowest thou didst kiss her hand this morning—I was not perfect then; but now, odsflesh! I can act the lover with any o’ ye. For the proof-behold. (He kneels, and reads from a paper, Most charming fair, Thy shape and air Have caus’d much smart In my poor heart— I must complain Of the sweet charms, Unless thou’lt ease my pain, And take me to thy arms. Heigho! E’nt that perfect? Sha’nt I do the business in a court way? ‘Tis verbatim from the last volume of love songs-‘ent it pretty? Enter Lady Alice and Dame Margaret, masked , and in mantles—the former very light blue, the latter red. R.S.E. Alice. In truth is it, most chaste Sir Tristram. I have been charmed with the echo of thy eloquence-let me luxuriate in the harmonious reality-go on. Sir T. I will. Most charming fair, So sweet and gay— (Stammers. Alice. Ti tum, ti tum, ti tum, ti tay. Sir T. Heigho! Speak for me— Most charming fair, Thy air and shape— The words stick in my wizen. Mon. Fair lady, words are but idle breath. Sir T. Words are breath. Mon. Thy lover hath perused thy letter. Sir T. He hath perused thy letter. Mon. He hath unriddled it. Sir T. Yes, he hath unriddled it. Mon. And would fain profit by this opportunity to prove his sincerity at the altar. Sir T. Yes, he’ll prove his sincerity at the altar-that is, marrying, you know. Alice. Gemini! Wilt thou absolutely run away with me, and wed me without my guardian’s leave? Mon. Thy true lover pants for the happy moment, when he shall say thou art his own. Sir T. Hem-thou art his own. Alice. Then, I’faith! I’ll take thee at thy word. Now do, my dear delicate sir, say something sweet and tender, in thy own original way, and thou shalt take this hand to the priest, ere the next rustle of the leaves. (Crosses to Monteagle, and leaves Margaret in her place, while Sir Tristram covers his face, thinking. Sir T. That will I, then. Brain, brain, be thou now prolific! Alice. (Aside to Monteagle.) I fancy thee, for that thou hast a merry heart; I trust thee for that I fancy thou hast an honest one. Away; let folly bask in the sunshine of his own conceit; and for the king’s anger, trust that to me. Mon. Yes, I will trust my life-my soul-my all-to thee, and think myself blessed in serving such a paragon. (Exit Monteagle and Lady Alice, R.S.E. Sir T. I have it- Most charming fair, Your shape and air, I do declare, Most charming fair, Your pretty hair Doth make me stare. Ah! What do I see? Even her mantle doth blush with the sublimity of my compliments—it used to be blue. Oh, most rosy rosebud! Dispense with my suspense—give me thy lily –white hand, and let us hie to-(She gives her hand,) Heigho! Mar. (Whispers) Heigho! Sweet Sir Tristram Sir T. Oh! What modesty! What Charms! Most charming fair, Thy shape and air Doth make me stare, And all that there. (Exeunt, R. Enter Walter Tresham, L. Wal. Where shall I hide me! Where shut myself from shame? Oh, for a cave, deep as this planet’s centre, dark as the house of death, and bounded by such terrors that the world should stand aghast to see me plunge therein, and dread to follow me! My wife, my babe! Yes, I must leave ye both—ye are no company for a wretch like me-I must not, dare not, meet ye more— Enter Master Richard Catesby, R. Cat. Or I mistake, or that same hurried step, and shrouded brow, bespeaks a traitor! Nay, start not—sure, thou art no mighty one! This shaking hand and agitated air assure me it can only be the weak, the paltry slave, that sold his friends-the miserable Walter Tresham! Stand forth, poor recreant! And know me for thy disgraced accomplice, Richard Catesby- disgraced alone by holding faith with thee-for sure no braver plot was e’er frustrated by a coward soul than this—thou knowest the hero Faux was taken ere the mighty act was finished. Wal. My prayers have risen to heaven, for that our souls are saved that hideous stain. Cat. ‘Twas by thy wife’s relation, the meddling Lord Monteagle. Wal. Just God, I am grateful; he will then have power to saave and cherish my poor wife and infant— Cat. ‘Tis fairly surmised that thou didst give him note of our intent. Wal. O, that I had the credit of such virtue!